Ship Manoeuvring

Proper procedures for anchoring and mooring

Clearing

anchors after a sea passage:

At the end of a sea passage, the anchor lashings are

removed. The cement and canvas over the spurling pipes are removed and so are

the metal covers,

Once the anchor is solely on

the bow stopper and the brake the anchor is said to have been cleared away

ready for use. In regard to the above – all loose material around

the spurling pipe and hawse pipe is cleared away since while anchoring these

cement or other pieces would fly off as dangerous missiles.

Executing

the anchorage plan

Check as far in advance as possible that the berth and

the planned approach to it are clear. Plot the anchored ships to confirm this.

Keep a constant check on the speed required to meet

the ETA.

Allow additional leeway for cross wind and tidal

streams as the speed of the ship is reduced, in order to make good the correct

line of approach. This particularly necessary in heavy ships,

which may have to reduce speed early in the approach.

As a general rule, try to anchor with the wind or

tidal stream (whichever is the stronger) slightly on the bow.

Normally plan to use the weather anchor. It is sometimes better to use the lee anchor

in places where the stream is so strong that the ship lies more easily to the

lee anchor. The lee anchor may be used

when the wind is across the stream, otherwise the ship may fall across the

weather anchor in the process of getting her cable, thus causing dragging. If other ships are already at anchor, it is

usually possible, by observing their cable, to see which is

the better anchor to use.

If anchoring with the wind abeam, it is often a good

plan to cant the bow into the wind using maximum rudder just before reaching

the anchorage position.

The anchor and the amount of cable to be used are

normally planned beforehand. Be prepared

to adjust both of these depending on the conditions encountered.

When on course for the anchorage, it is usually better

to give the Quartermaster the course to steer rather than to give him con

degrees. This leaves more time for

observing marks, ships, etc.

Information which is required:

Depth of water.

Nature of the bottom.

State of the tide on

anchoring.

Rise and fall of the tide

during the intended stay.

Tidal stream on anchoring.

Forecast and actual wind and

relative direction on anchoring.

Recommended anchor and scope

of cable.

Pilot station and their

distance from the ship.

Fix the ship on letting go the anchor-take beam

bearings first for accuracy—obtain a sounding and note the ship’s head and

time. The sounding provides a check that

sufficient cable is being used.

As the way is taken off the ship, the Navigating

Officer must observe what the ship is doing, either by beam bearings or by

objects in transit, and report this to the Captain.

Anchor

preparatory positions:

Prior arriving at the anchorage the anchoring crew

would go forward and after the usual checks would report to Bridge. And once

the order is received to prepare the anchor, the crew would continue to do so.

The order may be to keep the anchor ready from the

hawse pipe – used generally by pilots when unsure whether anchoring will be

required or not.

In this case the duty officer forward is supposed to

take the anchor on gear and walk back the anchor just slightly from the stowed

position and then again clamp the brake and release the gear. This ensures that

the anchor will go down once the brake is released.

If the order is to keep the anchor ready out side the

hawse pipe then the anchor is taken on the gear and walk backed just outside

the hawse pipe and then the brake is tightened and the gear released.

If the order is to keep the anchor in the ‘cock a

bill’ position then the anchor is to be walked back to the water level and kept

ready on the brake.

All lowering is to be done under power and never an

attempt is to be made by releasing the brake without engaging the gear of the

windlass.

‘Brought up’

In fair weather and light sea conditions:

The chain after having been paid out to its required

length and then held is expected to have anchored the ship.

The duty officer forward checks up on the cable – on

constant watching of the chain – it may be seen that the chain may have been at

medium stay and then after sometime (usually 5-10miutes) comes to short stay

and remains there.

Even for a final long stay, the brought up condition

would be a medium stay unless the weather is rough when it may be between long

and medium stay.

However if watching the cable for a further period of

5 – 7 minutes it is noticed to grow again, then a further period of observation

is required to see whether it comes to short stay or not.

If it stays at medium stay then it is said to be

‘brought up’ but if the cable alternates between short and medium or between

medium and long rapidly then it is certain that the anchor is not holding.

What happens is that the ship strains on the cable and

it stretches, if the anchor holds then the ship is slowly pulled in towards the

cable, else the anchor suddenly loses its hold and rapidly moves towards the ship

– above water we would see the cable stretch and then suddenly come to short

stay.

Bridge:

Whether or not the ship is dragging may be confirmed

by selecting a pair of fixed objects on the beam and in transit. Such objects need not be charted. The safest method of discovering whether or

not the ship is dragging is to fix by sextant angles or compass bearings. The fixes of the position of the bridge

should always lie within the bridge swinging circle drawn for the length of

cable veered. As mentioned earlier, if

they fall outside the ship is dragging.

Signals after anchoring

Once the vessel has ‘let go’ of her anchor the anchor

ball by day and the forward and aft anchor lights by night should be switched

on.

The navigation lights are switched off. Some ships are

provided with a station light forward, this may be switched on – provided that

this does not interfere with navigation.

Once the ship is brought up, all the deck lights are

switched on.

Anchoring

in deep water

Cable must be veered before letting go. The maximum safe speed of with cable veered

is limited, most ships should stop and take all their

way off, before veering cable.

For a larger ship anchoring in deep water is a new

concept of anchoring. It may be possible to veer the cable and then let go, but

in greater depths it may be prudent to walk back on the anchor cable until the

anchor is about to have reached the bottom. The anchor should then be taken on

the brake and the gear withdrawn and the anchor let go. This in the long run

would reduce the undue strain on the windlass system.

The holding ground is often poor. The depth of water is such that the standard

rules for the amount of cable cannot be used-for example, anchoring in 110

metres requires at least 13.5 to 14 shackles. A ship with, say, 9 shackles of

cable available will only be able to put about 4 shackles on the bottom in 110

metres of water. Thus, the holding power

of the anchor will be considerably reduced, perhaps by as much as 60% to 70%,

and account of this must be taken.

Having found a suitable position, the ship should

approach it at as slow a speed as effective steerage way will allow. Several shackles of cable may have to be

veered before letting go.

Different methods of anchoring

It is easier to anchor in the exact berth if steerage

way can be maintained up to the moment of anchoring.

Anchoring with headway and laying out the cable under

the ship is known as the running

anchorage.

When anchoring with headway, the speed when, letting

go should not be more than 2 to 3 knots over the ground. Too high a speed may strain or even part the

cable, while too low a speed will prolong the operation unduly.

The alternative to anchoring with headway is to stop

in the berth or just beyond it and then, having let go the anchor, go astern

laying out the cable. This is known as

the dropping anchorage; it is usually

adopted by all vessels, this method may well be more seamanlike than the

running anchorage.

The

advantages of the dropping anchorage over the running anchorage are:

The cable is laid out downwind and/or downstream (the

running method being into the wind and/or stream). This is the best direction for modern anchors

and cables, and there is less risk of damage to the protective bottom composition

and underwater fittings.

There is less risk of tumbling or slewing the anchor

as the ship lays back on the wind and/or stream after letting go.

There is less likelihood of dragging after letting go

through premature snubbing by the officer forward.

There is less wear on the hawse pipe and cable, and

less chance of damage, since the cable does not turn so sharply at the bottom

of the hawse pipe while it is being laid out.

The ship is ‘brought up’ more quickly.

The

disadvantages of the dropping anchorage as compared to the running anchorage

are:

Ship handling is compromised in the final stages

because way is taken off the ship in the last part of the approach.

The cable is not laid out in a bight and so cannot

absorb the strain gradually as the ship falls back on her cable.

The final moments of anchoring take longer.

Securing of anchors after anchoring

Once the ship has been ‘brought up’ and is riding to

the anchor, the bow stopper is lowered and the securing pin placed, the brake

is slackened a little to make the chain sit properly into position on the bow

stopper, and then is tightened full.

If the bow stopper cannot be fitted then the brake is

tightened full and a marker flag is tied to a link, should be visible from the

bridge (maybe through binoculars), to keep a check on the chain.

The hawse pipe covers are placed into their respective

slots, to prevent any unauthorized entry. However if the holding ground is not

good or if the weather is rough then it is best not to put the hawse pipe

cover, so because any movement of the chain would damage the covers and they

may get stuck in their slots thus causing delay in their removal once the time

arrives for heaving up.

Preparing to heave up and anchor cable markings

Once the crew arrives at stations forward, the power

on the windlass is to be checked.

The anchor wash water is started.

The water under the flare around the chain should be

checked for any foul up or any fishing vessels tied to the chain.

The windlass and the deck around should be checked for

any unusual damages.

The hawse pipe cover removed and the spurling pipe

checked for any obstruction.

The direction and the strain on the chain should be

reported to the Bridge.

The windlass should be in the proper gear (anchor lift

position/ double) and the weight is to be taken, and the bow stopper removed.

The brake is to be released slowly - in case the chain starts slipping the

brake is to be put back again.

Now the anchor is ready for heaving up, the chain

being controlled by the windlass alone. Once the order is received to heave up

the windlass is operated and the chain lifted up.

The duty officer constantly looks over the side from

the observation platform, he also checks up on the

movement of the chain on deck and should be aware to the voice of the crew on

deck.

At night the torch is used to good effect and in

general the signal is to wave the torch in circular motion for heaving up and

if the torch becomes stationary to awast heaving.

If there is too much mud on the chain then the chain

is picked up slowly to allow the anchor wash to wash down the chain.

The duty officer constantly reports the direction and

the strain on the chain as well as any other observations that he or the crew

may detect. The duty officer should check each joining shackle on deck as it is

brought up – include lead blocks as well as any clearance detected between the

parts of the shackle.

If time permits then the other crew is called upon to

clean and paint the cable markings.

The carpenter checks to see the main marking of

seizing wire – if damaged he replaces them.

The first half length of the chain immediately after

the anchor is not counted. The next joining shackle after this is called the 1st

shackle. The links immediately forward and aft of this joining shackle is

marked with a piece of canves being wound around the

stud of the link and fastened with seizing wire. Both the links are painted

white and the joining shackle red.

The next joining shackle is called 2nd

shackle. Here the mark is on the 2nd link before and after the

joining shackle and the same treatment is done to only the 2nd links

(forward and aft of the joining shackle). The paint is however applied to 1st

as well as the 2nd links forward and aft of the joining shackle. The shackle again being painted red.

Same with the 3rd shackle and so on.

AT the tenth shackle the while paint extends for quite

some distance. Since there are 10 links on either side of the joing shackle to be painted. The mark thjough

is only on the 10th link forwars and aft.

If the marks have been done at a dry dock then a stainless steel broad ring is

placed on the stud – instead of the canvas and seizing wire.

The report to the bridge may be like –

3 shackles on deck – cable leading 2 points on the bow

–medium stay - moderate weight, cable coming up easily, no

mud.

3 shackles on deck – cable leading across the bow - 2

points on the port bow (if the anchor is the starboard one) – long stay –

weight on the cable, cable not coming up easily, no

mud.

3 shackles on deck – cable up and down, cable coming

up easily, thick mud – have to slow down to wash.

3 shackles on deck – cable leading 2 points on the bow

– very long stay – excessive weight, cable not coming up, no

mud.

As the shackles come in, in addition to the reporting

by the duty officer, the carpenter also rings the bell according to the number

of the shackle – so with 3 shackles on deck he gives three distinct rings on

the bell.

Once the anchor is aweigh the duty officer so reports

and the carpenter rings a moderate continuous ring.

Securing anchors and preparing anchors for sea

Once the anchor has been washed the anchor is hove

right up into the hawse pipe, the bow stopper is lowered and the locking pin

inserted.

The winch is reversed a little to make the chain sit

properly into the slot of the bow stopper and then the brake is tightened and

the windlass gear removed.

The anchor chain at the deck level (hawse pipe) is

lashed with extra lashings as provided by the shipyard, if none are present or

if expecting heavy weather, then extra wire rope lashings are taken, The wire

rope to be used should be tested one, if an old (good condition) life boat

falls are available then this makes a very good extra lashing wire. This wire

is flexible and can be used by hand. A number of turns (figure of eight) are

taken around two sets of bitts. The free ends being fastened by bull dog clips

at least two fixed in opposite directions.

Generally the shipyard would have provide

lashing point as well as short length of wire attached to a bottle screw. These

should be well oiled and are the most efficient for lashing the anchor. The

wire should be tight.

Once the anchor is lashed the hawse pipe covers are

not placed but stowed under deck or in their stowage positions.

The spurling pipe area is chipped to remove any

residual remains of earlier cement.

The metal spurling pipe covers are placed around the

chain and over the spurling pile. The clips provided at the edges of the covers

should be hooked to the lips of the spurling pipe.

A new canvas cover is then placed over the metal

covers just fitted and is tied around the lips of the spurling pipe as well as

the chain. No empty spaces should be found.

Cement mixture is prepared and the entire cover is

covered with this mixture.

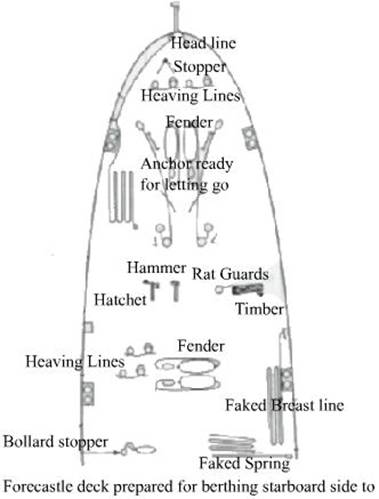

Preparations for berthing alongside

Prior berthing a ship, the mooring ropes have to be arranged faked down as required. If the ropes are on barrels of the winches then they have to be examined for any wear and tear. The wires if any have to be similarly checked. The tonsburg shackles attaching the wire to the rope tails are also to be inspected.

Once the inspections are over, the ropes are faked out

as required – and adequate length is faked so that the crew can easily pass the

lines when required.

Messenger ropes at least 2 of them and at least 2

heaving lines are to be arranged on the deck.

All the winches are to be inspected for any brake

lining damage and if hydraulic then any leakage and the tank levels.

The winches have to be tried out.

If the vessel requires portable fenders then the same

should be rigged at the most vulnerable points and then raised

up.

Large fenders are to be rigged at the break of the

forecastle deck and at the break of the accommodation.

No overside projections are allowed as such all

ladders and gangways are to be swung inside.

Equipment as shown in the figure are

to be ready at about the places shown.

Use of head ropes, stern ropes, breast ropes and springs

Head ropes are the first ropes that are sent from the

ship. Only in very few ports would any other line be passed as the first line.

The headline once passed fixes the ships head to a

point and then either a tug or the tide/ current is used to bring the ship

alongside.

The spring line is sent second, the work of this line

is to hold the ship in position. This line does not allow the ship to surge

forward, due to the action of the heaving headline.

Headlines and spring lines are generally all that is

required to hold a ship in position and alongside.

However it sometimes becomes necessary to send out

breast lines to keep the ship alongside. Note however that if the breast line

is not at 90° to the

ship the effectiveness of its usefulness is lost.

Stern ropes are sent after the forward headlines and

spring and serve the same purpose as that of the headline only in the opposite

way.

While heaving to keep the ship alongside the headline

and the forward spring form a lateral pulling arm while the stern line and the

aft spring form the other lateral pulling arm.

The headline and the aft spring being in the same

direction do not allow the vessel to move aft, while the stern line and the

forward spring do not allow the ship to move ahead.

And while all the lines are tight the vessel stays

alongside.

Safety measures to be taken when handling mooring ropes and wires

Mooring lines are made of synthetic material and thus

have a lot of inherent elasticity. Also the line when taken on the barrels at 4

to 6 turns may often slip and get heat damaged.

While heaving it is best to take a few extra turns and

then to stand clear of the rope and the barrel, since the rope often jumps out

of the barrels with devastating effect.

Never stand in the bight of a rope. During mooring stations with many ropes being handles simultaneously it sometime becomes difficult to figure out which rope is moving.

Never wear gloves when handling mooring ropes. These

may get caught in the turns and endanger the hand.

Always hold ropes being heaved from the underside with

the palm facing upwards. In case the rope jumps the hand would not come in the

way.

Wires

Always wear leather gloves – certified for handling

wire ropes.

Stay clear of all wires, these are not flaked.

During inspection check the condition of the wires.

While paying out the rope has a tendency to slow down

and speed up as the weight comes in.

Wires do not have much elasticity.

Do not cross a rope from the top always go under a

rope.

Do not pass ropes and wires from the same lead.

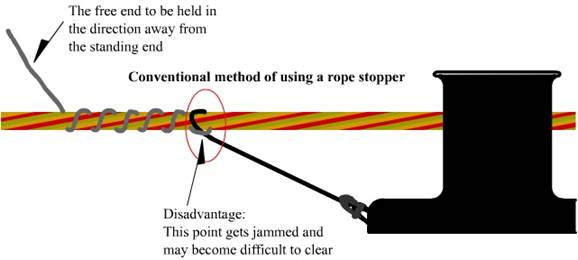

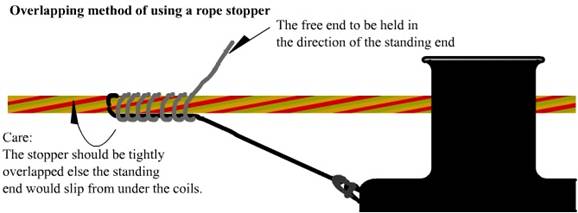

Taking a stopper on a rope

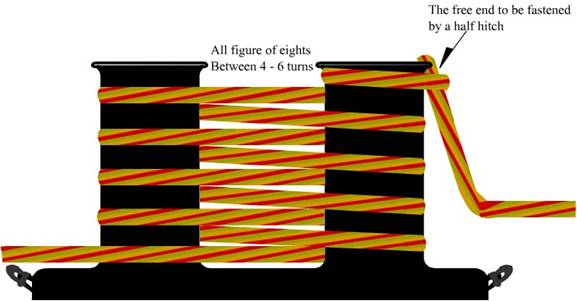

Making fast a mooring rope to bitts

Propeller

Clearance

The propeller area should always be kept clear of all

unwanted boats, floating ropes/ hawsers etc. A board stating ‘ Beware of

turning propellers’ should be fixed on either side of the poop deck railings.

Propellers are turned either to try out Main engines

on air and fuel or on turning gear.

In either case the danger lies in:

Personal hazard to people in

country boats and other wise.

Hazard to the shaft

connecting to the propeller that it may be fouled by a rope or such.

Ropes fouling a propeller are a serious incident since

it may lead to stern cooling oil leakage and barring the resultant oil

pollution, the cooling would be hampered. A fouled rope can only be cleared by

divers and thus is an expensive exercise – even if there is no damage to the

gland of the shaft.

In general, once a clearance is required by the Engine

room watch keeper, a responsible person with a communication unit should be

posted aft to see that the propeller is clear and he is not to leave stations

until the clearance is received from the Engine Room watch keeper. During the

entire operation the duty officer is to be kept apprised of the requirement of

propeller clearance and it should be included oin the

handing over and taking over responsibilities.

Again while on mooring stations, it is imperative to

inform the Bridge as to when the propeller is not clear (prior sending lines or

recovering them).

While berthing and unberthing

the propeller will be turned quite often, the duty officer attending aft

stations should prepare the lines for the tugs as well as the mooring lines so

that they may be sent out at the shortest possible time.

Making fast

tugs

There are two basic methods of tying up a tug.

Making fast the tug with

ships line.

In this the ship lowers the eye to the water line or

as required by the tug master (generally 2-3 metres above the water line). The

ship passes the rope after passing the rope through the bitt

(with a half turn- so that when the tug backs off prior tying up the rope does

not run out uncontrollably) where the plan is to make fast. The tug comes in

slowly and picks up the eye and puts it on the swivel hook. The tug then slowly

moves away from the ship taking in the slack, which is paid out by the ship.

Once the tug has enough rope she signals to make fast and the ship makes the

rope fast on the bitts. The ship then signals that the tug line is fast. The

tug initially stretches the rope and any slack in the turns on the bits now

pays out.

Care should be taken to see that nobody is in the

bight if there is one on the rope, also all should stand well clear of the bitt from where the rope is being paid out by an

experienced seaman.

Once the signal is to make fast, another hand woukld help in tying to the bitts with other men easing out

the coil from the stow position. A crowd should not be at the bitts.

Another method is a modification of the above. In this

case the tug asks for a heaving line to be thrown at the tug – attached to the

mooring rope. Once the eye is fast on the tug the operation is similar to

above.

Making fast

the tug with Tugs line

In this case the ship sends a heaving line attached to

a messenger line (24mm polyprop rope). The tug

attaches the tugs line to the messenger line. The ship heaves in the messenger

line on the winch. Care to be taken to see that the messenger line lead to the

winch passes across a bitt where the tugs line is to

be fast.

Once the eye of the tugs line comes on board, the

heaving is paused and a stopper is taken in the thugs

line below the eye.

The eye of the tugs line should be clear when the

stopper is taken on the tugs line, once the stopper has been rigged, the

messenger line is slackened gently and the weight shifted to the stopper.

The eye of the tugs line is quickly put on the bitts.

Making fast

to a buoy

Old method:

A messenger rope was tied to the mooring rope and the

messenger rope was sent to the buoy with the help of a heaving line or jolly

boat (boat with oars). The messenger line was taken through the eye of the buoy

and passed back to the ship. The ship put the messenger rope on the winch

barrel and heaved up on the same. The mooring rope was paid out and was kept

slack so that not too much weight came on the messenger rope.

Finally the eye of the mooring rope was at the buoy

where it was fastened or sent back on board through he

eye of the buoy to be fast on the ship.

In either case after the mooring rope was fast the

weight was taken on the mooring rope. The messenger rope

having been cast off and put to some other use.

Today:

Most buoy ports have a power boat which takes the

mooring rope lowered to the water level, it also takes some amount of rope on

the boat as slack, it then proceeds to the buoy the

ship paying out the slack.

Once the buoy people signal to heave up then only the

mooring rope is tightened.

Chain:

The ships chain is very rarely used for making fast to

a buoy these days. However in the River Hughli it was

quite common until the 70’s. A chain fasting barge used to come under the bows

or stern. And the chain was lowered on to the barge. The barge then proceeded

to the buoy, the ship paying out on the chain, keeping it just up and down. Too

much slack would cause a pile up under the ship, this was to be avoided.

Once at the buoy the mooring crew would make fast the

chain to the buoy and then signal to heave up, the slack was picked up under

the direct command of the pilot/ mooring master.

The day prior lowering the chain the anchor was

lowered out of the hawse pipe and lashed between the hawse pipe and the bow

stopper and the chain was cut at the joining shackle and the chain without the

anchor was lowered to the water level.

The entire process of making fast to the buoy would

take anything from 4-6 hours. This was a common practice on days when a bore

tide was expected. The stern had coir rope springs attached to blocks specially

brought from shore for this purpose.

Singling up

Once the command is received to single up – generally

the number of lines would be specified – if nothing is mentioned then it should

be clarified. Generally the departure meeting would have sorted out this.

The singling up should start from the weakest lines

being cast off first (these lines would not have been the first lines while

berthing). The other lines that are cast off are the lines left on the winch

barrels (due to paucity of bitts).

The last headline that would be held on to should be a

good one and have a good lead from the fairlead to the winch barrel – it should

preferably be on the side opposite to the side on which the spring has been

made fast.

This ensures that the station can pick up both the

spring as well as the head line after casting off together and not too much

time is lost – as will happen if one line is picked by one after the other.

The spring or other line that has been held on to

should similarly a good one and should have a good lead.

Note for both the lines adequate length should be kept

in readiness since sometimes the lines have to be paid out, thus the headline

and spring free ends should not be submerged under other lines when they are

picked up.

From the buoys:

Here too the same precautions are valid. Here a tug will

be fast to pull out the ship and in the absence of spring the headline and the

tugs line should be on opposite sides to facilitate the picking up of both

simultaneously.

Again the last line should have adequate spare length

to slack away prior casting off.

Casting off

a rope

Slipping a wire rope – generally for a tug is one of

the most dangerous actions and numerous cases have occurred where people have

been hurt.

Once the tug or other line has been slackened until it

is up and down in the water. A messenger is rigged to the winch barrel and the

end of the messenger is used to take a stopper on the wire.

Care the lead of the messenger should follow the way

of the wire as it has been fastened on the bitts.

Once the stopper (conventional) has been taken the

messenger is heaved up with the wire. As the wire becomes slack on the bitt, a second normal rope stopper is fastened and a couple

of hands are sent to slip it over the bitts. Once all is clear the messenger

rope stopper is gently slackened until all the weight is on the short stopper

and the messenger rope stopper is removed. When finally the

short stopper is cast off.

Many ships take a short cut and do away with the short

stopper and rely on the messenger rope stopper, but in this there is a danger

of the messenger rope slashing back after the wire rope is cast off from it.

This may injure someone.

Stowage of

ropes

The mooring ropes when they are taken in on board are

wet. As such it is not advisable to stow them under deck unless the weather

predicted is very rough.

For short voyages:

The mooring ropes are stowed on deck, on wooden

gratings. The ropes are neatly coiled, the coil starting with the end of the

rope kept clear of the grating and then coiling from a tight small circle and

then expanding to the edge of the grating. Once the edge is reached, the rope

is coiled inwards towards the centre and then again as the inside coil is

reached it is moved outwards. Finally the free end of the rope is put on the bitt.

A stout piece of rope (24 mm) is then used to lash the

rope coil to the grating. The grating being fixed to the deck

or lashed independently.

For long voyages:

A day after the mooring ropes were stowed on deck the

ropes are sent below deck, where the system of grating is the same as on deck.

Only the ends of the ropes are tied together with a

piece of rope to facilitate a continuous length of rope to be taken down as

well as taken up. Generally the stoppers are utilized for the tying up.

Thus the stoppers are also cared for by not leaving

them on deck.

For ropes stowed on winches:

After the rope has been reeved in the free eye is put

on a bitt. Once draining is done the rope is covered

by a adequate size of canvas (usually after 24hrs) the

canvas is tied down.

For wires:

The wire after being reeved in is allowed to drain.

Once draining is complete the wire is covered by a canvas cover.

Prior putting the canvas cover the top layers are

generally oiled with some excess oil/ grease, this ensures that if the wire is

not going to be greased during the voyage the oil would seep down to the other

layers.

Pilot Ladders

This is a portable ‘roll-up’ ladder that can be hung

over the ship’s side for embarking and disembarking of the pilot and others

when the weather turns too choppy for the accommodation ladder to be used.

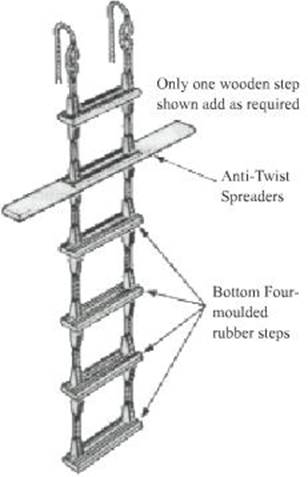

The ladder when rigged should terminate 300mm above the surface of the water in calm conditions. The pilot ladder is constructed of serrated; non-slip treads with side ropes threaded through their ends. The bottom four treads are made of moulded rubber and the remainder from hardwood; winnets (chocks) are seized between the two parts of each side rope to keep the treads in position. 3m x 20mm polypropylene securing lanyards are spliced to thimble eyes at the inboard end of the ladder, the ladder should be secured by shackling the thimble eyes direct to suitable strong points in the ship. To prevent the ladder twisting, 1.8m anti-twist spreaders with an integral serrated tread are fitted to the ladder at regular intervals, depending on the length of the ladder,

Total number of treads in ladder Position

of spreader

6-13 As the 5th tread

14 As

the 5th and 12th tread

15 As

the 5th and 13th tread

16-22 As the 5th and 14th tread

23 As

the 5th, 14th and 21st tread

24 As

the 5th, 14th and 22nd tread

25-30 As the 5th, 14th and 23rd

tread

While embarking a pilot, two 24mm manila or staple

spun polypropylene manropes must be provided.

They must be securely hitched to the handhold stanchions or other

suitably positioned fixtures and should extend for the length of the ladder,

terminating with a manrope knot in the end of the rope.

Pilot ladders are crucial equipment for embarking and

disembarking the pilot, and should as far as possible be not used for anything

else.

The pilot ladder is first to be inspected for any wear

and tear especially if any of the chocks are loose.

Once that is over the ladder is lowered over the side

to the desired level. The end ropes of the pilot ladder are now passed through

the lugs welded on deck and are a clove hitch is made over the step ropes in

such a way that a chock would take the weight. The free end is brought to the

lug on deck and a clove hitch is again made there. This is repeated for both

the side ropes of the ladder.

The stanchions are then fixed on to the gunwale and

the man ropes hung out.

Lighting is important and if the ship is not provided

with a permanent fixture then a cargo light (portable) has to be hung over the

side with the light falling on the ladder.

The equipment at the ladder site should include the

following:

Life buoy with a SI light

If the pilot ladder station is not fitted with a fixed

lighting system then portable cargo lights are to be hung overside.

Gant line

Heaving line

A canvas bag

A safety harness

A life jacket

The rigging of the pilot ladder is to be supervised by a responsible officer (with communication unit), who is to check that all the requirements as to the above noted points are covered and if any extra precautions are required as per the pilot’s instructions or the Masters instructions.

Fendering

A ship going alongside another ship or a jetty

requires a strong crushable fender to absorb any impact, but the fender must be

sufficiently unyielding to provide protection and sufficient separation to

allow for any overhanging structures, etc.

For boats and other small craft whose sides are strong in comparison

with the weight of the vessel, fendering presents no difficulties and any soft

fender is adequate. For larger vessels

fendering must be sufficiently robust to withstand the crushing of the weight

of the ship, and it must be large enough and sufficiently resilient to spread

and absorb the shock over a large area of comparatively weak hull plating. Fenders must be placed where the hull can

best withstand the impact; to some extent this applies to all ships, but in

modem ships they must be placed at specified positions where the hull is

strengthened by additional stiffeners near the waterline; tally plates (often

stenciled) on the weather deck show the limit of the stiffening. The fenders described below are divided into

three categories, those that are - fixed to the structure or jetty of a pier,

those that are mobile and provided in port (too heavy for ships) and those that

are portable (carried in ships).

Fixed Fendering. The solid walls of berths and the piles of

jetties have vertical logs of timber attached to protect the masonry/ concrete

and to provide fendering to ships alongside.

In some ports no other form of rendering is provided, but the use of

suspended rubber units is increasing. In

a tidal port, to lessen the impact when a ship is brought alongside, some

springing device is included between the timber and the masonry.

Port Fenders.

Catamaran. This is a stoutly constructed

rectangular wooden or steel raft used in dockyards between ship and jetty. The bearing surfaces are usually fitted with

rubber rubbing pieces.

Large Pneumatic Fenders. These are increasingly being used instead of others for ships

lying alongside a dock wall or other ships, although they are not suitable for

use on piled jetties unless the area on which they will bear has first been

sheeted over with steel plate or similar Material to ensure the load is

spread. The fenders are manufactured

from textile reinforced rubber, and there are two types in use, the low

pressure type with a diameter of 2.3m and a length of 12m, Pattern number, and

the high pressure type, produced in various sizes, obtainable only by local

purchase. They also known as Yokohama Fenders and are seen mostly during STS

operations between tankers.

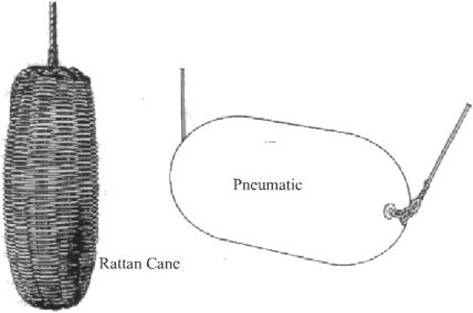

Portable Fenders

Rattan Fenders are made of rattan cane. They are light, clean and suitable for coming

alongside when other fenders are not available.

Two sizes are available, 1.2 x 0.5m, and 0.6m x 0.3m.

Portable Pneumatic Fenders. There is now an assortment of easily portable

pneumatic fenders available. They are ideal for light-hulled ships lying

alongside a dock wall or other ships but they must not be used when going

alongside unless great care is taken

The most common sizes in use are 0.96 x 2.2m, and

0.64m x 1.2m.

Other homemade fenders include fenders made from

wooden logs served with cordage and passed through a number of old motor

tyres. A wire lanyard is fitted to each

end so that the fender can be slung horizontally. It is a durable fender, but very heavy.

Old motor tyres, timbers are all suitable materials for making jury fenders.