| Curves of Stat. Stability | List | Free Surface Effetcs | Trim |

Stability

Displacement

Mass, Weight, Force and Gravity

Mass is the

amount of matter that is contained within a body.

The S.I. units of Mass are:

Grammes

Kilogrammes = 1000 grammes

Metric ton = 1000 kilogrammes

Force is the product of Mass and acceleration

The S.I. Unit of force is:

Kilogramme m/ s2 or Newton (N)

Example: The car hit the tree with a great force. What

would be the great force, this may be calculated by

applying the above.

However the car may not have been speeding or increasing the acceleration but may have been traveling at a constant speed, in that case we come to Momentum

Momentum is

the product of Mass and velocity.

So in case of nautical terms the constant velocity of

a ship is of great importance.

If a ship bangs against a jetty with some velocity

then there will be damage to the jetty but if the same ship reduces her speed

or velocity then the impact damage will be considerably less.

Coming back to Mass and Weight

Weight and Mass are often confused in everyday life.

Weight is actually the resultant force that acts on a

body having some mass.

Weight is thus a product of the mass of the body and

the acceleration due to the earths gravity.

So, the S.I. Units of Weight should actually be kg

m/s2 or Newton (N)

Here since the acceleration due to gravity is known as

9.81m/s2

Therefore we may write:

a mass of 1 kg having a weight of 1kg 9.81 m/s2 as 9.81 kg m/s2

Or simply 1 kgf, which is saying 9.81 N

Or conveniently since 9.81 is constant on the surface

of the earth

We may write the weight to be:

1 kgf, this is the force that is being exerted on a

mass of 1 kg.

But if have to express this in

9.81 N

However again since the gravity factor is common the

unit of Weight is also expressed as kg.

Thus:

1 tonne = 1 metric ton force = 1000 kgf

Or 1 tonne is a measure of 1 metric ton weight.

Moment is the product of force and distance

The S.I. Units of Moment is the Newton-metre (Nm)

Since we have seen that force is expressed in kgf or N

and the S.I. Unit of distance kg is the metre

Thus, 9.81 N = 1 kgf

And, 9810 N = 1000 kgf or 1 tonne

So, the unit generally used for large moments is the tonnes-metre

Pressure is the force that acts on a body to cause it

to change in some form.

If it does not change and there is room for it to move

then it does so.

Pressure is thrust or force per unit area and is

expressed as:

Kilogrammes-force units per square metre or

Kilogrammes-force units per square centimetre or for

larger pressure in tonnes-metre (t/m2)

Density is defined as mass per unit volume or is

expressed as unit of mass per unit of volume

Or grammes/ cubic centimetre

(gms/cc or gms/cm3)

Fresh water has a density of 1 gm/cm3 or

1000kg/m3

Both are correct since:

1 kg is 1000 gms

and 1 metre is 100 cm, since we are talking of cubic quantity 1 cubic metre

would be 100x100x100 cubic cm

So to equate it would be 1000 kg/m3

Or 1 t/m3

Thus the density of FW may be expressed as 1gm/cm3

or 1t/m3

Relative

density is a factor without any unit.

Relative density is expressed as the density of the

substance divided by the density of FW

Thus the RD of FW would be 1/1 or 1

And the RD of SW would be 1.025/1 or 1.025

So basically it is expressed as the same numerical

value but without a unit.

Archimedes found that when a body is immersed in water

then the volume of water that overflowed as a result of this immersion was

equal to the volume of the body.

However the weight of the body plays an important part

in this.

Although the volume of the displaced water is the same

as that of the body the weight may not be the same.

Let us assume that a log of wood of dimension 1metre

by 1metre by 12 metres is taken (thus the volume is 12 metre3, or 12

cbm), let the weight of the log be 8 t. (assumed density of the log at 0.667

t/m3)

This log when it is fully immersed (using external

force) in a tank full of water will make some water overflow, the quantity of

water that would overflow would be 12 metre3, or 12 cbm

But the weight of this water would be 12 t at the

density of 1t/cbm

So we see that the weight of the water is more than

the weight of the fully immersed log of wood and so the log will float.

But at what level?

Now if we remove the force that was holding the log

underwater the log will bounce back to the surface and only a portion of the

log will remain underwater.

This amount will depend on the volume that it

displaces and the weight of that displaced water. Both have to be equal.

If we assume that only 67% of the log is immersed

(12cbm x 0.67) then the volume of the water displaced would also be 8 cbm and

its weight would be 8 t and that was the weight of the log.

So the log would float in a state of equilibrium

However the log would still be capable to taking extra

load, and we can place weight on the log up to a maximum of 4t, any weight

beyond that, and the log would sink.

Let us work out the same example with a bar of iron of

the same dimensions, thus the volume would be 12 cbm and at a density of iron

at 7.86 gm/m3 the weight of the bar would be 94t.

The volume of water that this bar would displace would

be 12 cbm but the weight would be only 12 t.

This being a much lesser figure than the weight of the

iron bar, the iron bar would sink.

Can we now make this bar of iron float?

Yes, we can but we then need to flatten it out to a

sheet of iron.

We then need to bend the four edges so that the sheet

is turned into a open cardboard box.

This will give the iron sheet a much larger volume, the empty space on top of the sheet would also

contribute to the volume but without adding to the weight (assuming the weight

of air to be negligible)

The sheet + air combination however has the same

weight.

Now it will float on the water at a level as

determined by the weight of water that it would displace at that level.

Centre of

Gravity is the point of a body at which all the mass of the body may be assumed

to be concentrated.

The force

of gravity acts vertically downwards from this point with a force equal to the

weight of the body.

Basically

the body would balance around this point.

The Centre

of Gravity of a homogeneous body is at its geometrical centre.

Buoyancy and Centre of Buoyancy

So what makes the log or the open box iron sheet float.

The fact that they are on the surface of the water is

due to the earth’s gravity or the weight of the body.

That it does not sink is due to Archimedes’ principle.

We may also say that a force is pushing up the box.

This force is dependent on the volume of the box within the water as well as

its weight.

This force is termed as the force of Buoyancy.

It will act in case of a uniformly loaded box shaped

vessel through the centre of gravity of the underwater volume of the box.

However if the loading is not uniform, by which we

mean that if say only the fore part is loaded with some other weight then

obviously the underwater volume of the box will change and the centre of

buoyancy will pass through centre of gravity of the new underwater volume of

the box.

Centre of Buoyancy can be defined as the geometrical centre of the underwater volume and

the point through which the total force of buoyancy may be considered to act

vertically upwards with a force equal to the weight of the water displaced by

the body.

Reserve Buoyancy

We have seen the condition of the sheet of iron, which

was turned, into an open cardboard box, which floated very nicely on the

surface of the water.

What happens if you now decide to tilt the box,

depending on how high the edges are the water will enter the enclosed area and

the combination of sheet+ air will become sheet + air + some water.

This may make the box much more heavier

than the weight of the volume of water displaced and the box would sink.

Thus we require to put a

water tight cover on the open box. This would ensure that no water would enter

the open space within the box and the sheet+ air combination would remain

intact and the box would float perpetually.

Thus what we have created is Reserve buoyancy.

A ship in a sea way floats on water, which may be calm

and also may be rough.

When in a rough seaway the ship rides the waves, the

waves support sometimes the ends of the ship and then at the midway mark.

In either of the case the ship would have a tendency

to sink to a lower level since the weight of the ship and that of the water

that it displaces would be different.

Thus the requirement for a

ship to have reserve buoyancy, to meet any eventual sea condition where more

sheet + air combinations would be required to be brought into use.

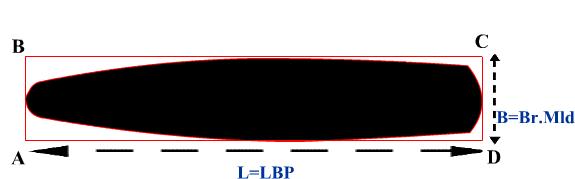

Coefficient

of fineness of water-plane area (Cw):

A ship

floats on water. If at the water line the ship were to be cut off then the area

at the water level is known as the ships water plane

If we now

divide this area of water plane with an imaginary rectangle having the length

similar to the maximum length of the water plane and breadth similar to the

maximum breadth of the water plane then this ration is termed as the

coefficient of fineness of water plane area or Cw

Cw = Area

of water-plane/Area of rectangle ABCD

Similarly

if we know the Cw at a particular draft then we may find the actual water plane

area of the ship by measuring the maximum length and the greatest breadth.

Area of the water-plane = L x B x CW

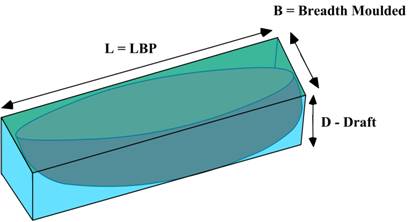

The block

coefficient of fineness of displacement (Cb):

In exactly

the same manner as we obtained the water plane area, if we were to measure the

volume of the underwater part of the ship and divide this with the volume of a

box having its length as that of the ship at that particular draft and breadth

of the box as the maximum breadth of the underwater volume, then we would

arrive at a ratio.

This ratio

is termed as the block coefficient of fineness of displacement,

or Cb

Cb at any

particular draft is the ratio of the volume of displacement at that draft

to the the volume of a rectangular block having the

same overall length, breadth and depth.

Knowing how

the Cb was arrived at, we understand that for a box shaped vessel the ratio of

Cb be 1.

Also finer

the lines of a ship the lower would be the Cb.

Thus a VLCC

would be tending towards 1, whereas a slender yacht or a warship would be

closer to 0.5.

Again this

value of Cb would depend on the draft of that particular ship, since at the

load draft a ship, even a small one appears quite box shaped but as the light

draft is approached the fine curvature of the ship is apparent.

For

merchant ship, this value (depending upon draft) will range from about 0.500 to

0.850, with some typical values as shown below:

ULCC – 0.850 General Cargo ships – 0.700

Oil tankers

– 0.800 Passenger ships – 0.625

Bulk

carriers – 0.750 Container

/ Ro-Ro – 0.575

Tugs

– 0.500

Cb = Volume

of displacement / L x B x draft

Therefore

as in the case of Cw, the underwater volume of a ship may be found at that

particular draft by:

Volume of

displacement = L x B x draft x Cb

The value

of Cb is used to determine the carrying capacity of a Life Boat.

In figure,

the shaded portion represents the volume of the ships displacement at the draft

concerned, enclosed in a rectangular block having the same dimensions.

SHIP’S LIFEBOAT BLOCK COEFFICIENT

The problem

of loading/ declaring the number of persons that it can carry in a Life Boat is

that we do not have any load line marks to guide us.

And even if

there was one it would be difficult to embark looking at the load line mark.

So how is

the number of passengers determined for a life boat.

The block

coefficient of the boat is taken, in this case there is no need to launch the

boat in the water and note the draft.

Say the If

we accept that the Cb of wooden lifeboat is 0.6

Therefore,

volume of the entire lifeboat would be given by

L x B x

draft x 0.6 cubic metres

Now that

the volume of the lifeboat has been found, the next step is to determine the

number of persons that it would safely carry.

To

determine this the following is used and result is the

closest whole number so obtained.

Volume of

the boat / volume of each person

(both in cubic metres)

Here the

size of the person is generally not taken into consideration but the volume is

adjusted with the length of the boat.

For

lifeboat lengths:

7.3 m or

more the volume of a person is taken as 0.283

4.9 m the

volume of a person is taken as 0.396

For

intermediate boat lengths the values

are interpolated.

Effect of

change of density on draft when the displacement is constant

It has been

already explained that the body floats on water at a particular level/ draft,

as long as the weight of the body is equal to the weight of the volume of water

that is displaced by the underwater volume of the body.

Thus the

volume of the water depends on the underwater volume of the body, and

The weight

of this volume of water depends on the density of the water.

Thus when a

ship moves from water of a higher density to a water of lesser density, the

weight of the water volume will become less.

To

compensate for this weight loss an additional volume of water has to be displaced,

this is only possible if the underwater volume of the body is increased.

So the

body/ ship will sink lower in the water of a lesser density, or the draft will

increase.

For box

shaped vessels since the shape is uniform all the way from the top to the

bottom, the walls being all vertical, it is easy to calculate the sinkage or

the rising of the vessel with the change in the density.

The resulting effect on box shaped vessels will be:

New mass of

water displaced = Old mass of water displaced

New volume

x New density = Old volume x Old density

New Volume = Old

density

Old Volume New

density

But volume

= L x B x draft

L x B x New draft = Old density

L x B x Old draft New

density

New draft = Old

density

Old draft New density

The resulting effect on ship shape vessels will be:

New

displacement = Old displacement

New

volume/Old volume = Old density/New density

Due to the

fact that the ships underwater shape is not like a box shaped vessel, the

underwater volume does not linearly change.

To find the

change in draft of a ship shape, the FWA must be known. This is the number of

mm that a ships draft changes when passing from SW to FW.

FWA (in mm)

= Displacement/(4 x TPC).

When the

density of the water lies between these two (SW & FW) then the value (in

mm) that the ships draft changes when she enters the SW is called the Dock

Water Allowance.

DWA (in mm) = FWA (1025 – DW density)/25

Keeping the

draft constant, in effect means that no load has been added or removed.

But if the

draft remains unchanged, even when the density of the water has changed implies

that some change to the displacement has occurred.

Let us

consider:

A ship

floats in the water at a certain draft, therefore the

underwater volume of the ship displaces an equal volume of water. This volume

of water when multiplied with the density of the water gives us the weight of

the water, which again is equal to the weight of the whole ship.

Now if the

density of the water is reduced (travelling from SW to FW), the following would

happen:

The weight

of the displaced water would become less. And consequently to compensate for

this loss in weight an additional volume of water would have to be displaced.

To get an

additional volume of water displaced means that the unde5rwater volume of the

ship has to increase.

If we do

not want the underwater volume of the ship to increase then we have to remove

weights fr0om the ship.

Thus we see

that to keep the draft constant, in a changing density scenario we have to

either lighten the ship or we have add more weights to the ship.

However,

since the draft has not changed, the volume of water displaced also has

remained unchanged.

New vol. of water displaced = Old vol. of water

displaced

New displacement = Old displacement

New density Old

density

New displacement = New density

Old displacement Old

density

Tonnes per

centimetre immersion (TPC)

This is the

mass that must be added/ or removed to a ship in order that the mean draft of a

ship changes by a value of ONE centimetre.

The figures

that are given are for SALT WATER only and corrections have to be applied for

obtaining the values in FW and in other dock waters.

The TPC is

not constant for the ship in all states of loading. The TPC changes as the

underwater form changes, thus the TPC’s are given

against the drafts.

For every

draft there is a different TPC, the most notable changes are between the light

draft and the half way load draft, close to the summer draft the values changes

are very small..

The Tonnes

per Centimetre is therefore dependent on the underwater form of the ship and

this is determined by the water plane at the surface of the water.

So to

calculate the TPC the water plane is essential.

TPC =

(water plane area x density of water) / 100

water plane area (WPA) is in m2

Density is

in t/m3.

Now let the

mass ‘w’ tones be loaded such that the draft increases by 1 cm & the ship

now floats at new Waterline W’L’

Since the

draft increase is by 1 cm the mass loaded is equal to TPC.

Also as the

displaced water quantity increases by some amount, this weight of extra water

displaced equals to TPC as well.

Mass = Volume x Density

= Area x

1/100 x 1.025 tonnes

=

1.025A/100 tonnes

TPCSW = 1.025 A/100

TPCFW = A/100

TPCDW = (RDDW x TPCSW )/1.025

Note: TPC

is always stated for Salt Water unless otherwise specifically mentioned.

Effect of draft and density on TPC

Since the

TPC as has been seen is dependent on the 2 factors:

1. Water

plane area – which determines the underwater volume of the ship

2. And the

density of the water on which the ship is floating

Thus if any of these two factors change the TPC will be affected.

For box

shaped vessels the 1st factor is not applicable since the shape is

uniform all the way from the top to the bottom, the walls are all vertical. The

2nd factor of density needs to be attended to. As the density

increases the TPC also increases.

However for

most ships being ship shaped meaning not box shaped, means that both the

factors affect the TPC. The water plane area would change as the ship sinks

deeper into the water or is lightened. Also the density affects the TPC in the

same way as for a box shaped vessel.

TPC Curves

TPC is

calculated for a range of drafts extending beyond the light and loaded drafts.

This

calculated TPC is then tabulated or plotted in a graphical form and these

graphs are called the TPC curves.

On board a

ship the TPC’s are given in both a tabulated form

alongside the drafts as well as in a graphical form.

Displacement Curves

Displacement

of the ship in SW (1.025) at various drafts is given in both a tabular form as

well as in a graphical form.

A

displacement curve is one from which the displacement of the ship at any

particular draft can be found, and vice versa.

Fresh Water

Allowance (FWA)

In the

basic principle of why a ship floats it is understood that the weight of the

volume of water displaced by a ship is equal to weight of the entire ship.

The volume

of the displaced water is again equal to the volume of the underwater volume of

the ship.

Now when

the weight of this displaced water is calculated we take the product of the

volume of the water and the density of the water.

So, if the

density of the water changes, then the weight of the displaced water changes,

the weight of the ship remaining unchanged.

Thus to

keep the ship floating something has to be adjusted and adjustment is in the

underwater volume of the ship.

So a ship

floating in waters of different densities will do so at different levels.

Thus to

keep the ship floating something has to be adjusted and adjustment is in the

underwater volume of the ship.

So a ship

floating in waters of different densities will do so at different levels.

So we can replace the word level by the nautical word

‘draft’

Thus we may

now define Fresh Water Allowance as the amount in millimetres by which a ships

MEAN DRAFT changes when she moves between SALT WATER and FRESH WATER.

As a ship

moves from SW to FW, the weight of the displaced water reduces – RD of SW at

1.025 and FW at 1.000, so additional volume of water is required to float the

ship, this means that the underwater volume of the ship has to increase so the

ship sinks lower to compensate the above. So the draft increases.

In the same

way if a ship moves from FW to SW, the weight of the displaced water would be

more than the weight of the ship, so the weight of the water has to be reduced,

this may be reduced if the volume of the water is reduced, this again depends

on the underwater volume of the ship, so the underwater volume of the ship is

reduced.

And so the

ship rises a little and the draft of the ship reduces.

FWA (in mm)

= Displacement/ 4x ( (water plane area x density of

water) / 100)

Or FWA =

Displacement / ( 4 x TPC)

Effect of

draft on FWA:

For box

shaped vessel, FWA is the same at all drafts.

For ship

shaped vessels, FWA increases with draft. As the draft increases, both the

displacement and the TPC increase, but the rate of change of displacement is

higher than that of the TPC.

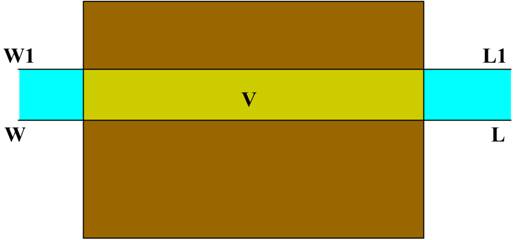

Derivation of the FWA formula

Consider a

ship floating in SW at load Summer draft at waterline

WL.

Let volume

of SW displaced at this draft be ‘V’.

Now let

W1L1 be the waterline for the ship when displacing the same mass of fresh

water.

Let ‘v’ be

the extra volume of water displaced in FW.

Total

volume of fresh water displaced will be V + v.

Mass =

Volume x density

Mass of SW

displaced = 1025V

Mass of

fresh water displaced = 1000 (V + v)

But mass of

FW displaced = Mass of SW displaced.

1000(V + v)

= 1025V

v = V/40

Assume that

‘w’ is the mass of SW in volume v and ‘W’ in volume V,

Then,

replacing the factor

as obtained above we get:

w = W/40

But w is a factor that is a product of the FWA and the

TPC

Now since

the FWA is in mm and the TPC is in cm, they both have to be converted to metres

Thus:

W = (((FWA

mm x 100)cm X TPC cm) / 100 ) metres

Simplifying

we have:

w = (FWA x

100 x TPC) / 100 = W / 40

Or (FWA x

TPC) = W / 40

But w = TPC

x (FWA/10)

Hence W/40

= TPC (FWA/10) or FWA = W/(4 x TPC).

Where ‘W’ =

Loaded SW displacement in tonnes.

Mass =

Volume x density (22*100*12)/100=242=W/40

W=9680

9680/4/12=2420/12=242/1.2=22

Mass of SW

displaced = 1025V

Mass of

fresh water displaced = 1000 (V + v)

But mass of

FW displaced = Mass of SW displaced.

1000(V + v)

= 1025V

v = V/40 TPC = (water plane area x density of

water) / 100

Assume that

‘w’ is the mass of SW in volume v and ‘W’ in volume V,

Then,

replacing the factor

as obtained above we get:

w = W/40

Displacement

= FWA x ( 4 x TPC)

But w = TPC

x (FWA/10)

Hence W/40

= TPC (FWA/10) or FWA = W/(4 x TPC).

Where ‘W’ =

Loaded SW displacement in tonnes.

Dock Water

Allowance (DWA)

As a ship

sails the seas the SW density is assumed to be constant at 1.025 gms/cc, however the density of the SW is never the same

everywhere, especially in partially enclosed salt water bodies, this does not make much difference since the depth of the

water is very substantial.

However

when a ship enters a river from the sea the density of the water changes from

SW to FW, gradually. The density of the river may never attain pure FW

conditions and may be in between.

Thus the need to calculate this intermediate correction for the new

density.

Docks

(enclosed port areas containing jetties) have water that is intermediate

between SW and FW, the water is brackish and may have

a density of 1.010 gms/ cc.

Thus Dock

Water Allowance is similar to FWA and is the amount in millimetres by which the

ships mean draft changes when a vessel moves between a salt water and dock

water.

Dock water is the water whose density is neither that of fresh water or

salt water but in-between the two. RD between 1.000 and 1.025.

To get the

correction in millimetres the formula that may be used is:

(Please

note however that the DWA allowed for should be for the minimum density that

will be encountered by the ship while proceeding to the dock – this as a safety

factor)

DWA = (FWA (1025 – density of dock water)) / 25