| Wind Pressure Sys. | Structure of a Depression | Anticyclone | Weather Services | TRS |

Meteorology

Structure of Depressions

DEPRESSIONS

A depression, also known for synoptic purposes as a

low, appears on a synoptic chart as a series of isobars roughly circular or

oval in shape, surrounding an area of low pressure. Depressions are frequent at

sea in middle latitudes and are responsible for most strong winds and unsettled

weather, though not all depressions are accompanied by strong winds.

Depressions vary much in size and depth. One may be

only 100 miles in diameter and another over 2,000; one may have a central

pressure of 960 millibars and another 1,000 millibars.

In the N (S) hemisphere the winds blow around an area

of low pressure in an anti-clockwise (clockwise) direction.

There is a slight inclination across the isobars

towards the lower pressure. The strength of the wind is closely related to the

gradient across the isobars, the closer the isobars the stronger the wind.

Depressions may move in any direction though many move

in an E direction, at speeds varying from nearly stationary to 40 knots.

Occasionally, during the most active stage of its existence, a low may move as

fast as 60 knots. Lows normally last around 4 to 6 days and slow down when

filling.

The following is a brief general description of

depressions and the associated weather in temperate or middle latitudes of the

two hemispheres. It must be emphasized,

however, that individual depressions in different localities differ

considerably from one another according to the temperature and humidity of the

air currents of which they are composed and the nature of the surface over

which they are traveling.

A falling barometer indicates the approach of a

depression.

In the N (S) hemisphere, if a depression is

approaching from the W and passing to the N (S) of the ship, clouds

appear on the W horizon, the wind shifts to a SW (NW) or S (N) direction and

freshens, the cloud layer gradually lowers and finally drizzle, rain or

snow begins. If the depression is not

occluded, after a period of continuous rain or snow there is a veer (backing)

of the wind at the warm front. In the

warm sector, the temperature rises, the rain or snow eases or stops, visibility

is usually moderate and the sky overcast with low cloud.

The passage of the cold front is marked by the

approach from the W of a thick bank of cloud (which however cannot usually be

seen because of the customary low overcast sky in the warm sector), a further

veer (backing) of wind to W or NW (SW) sometimes with a sudden squall, rising

pressure, fall of temperature, squally showers of rain, hail or snow, and

improved visibility except during showers.

The squally, showery weather with a further veer

(backing) of wind and a drop in temperature may recur while the depression

recedes owing to the passage of another cold front or occlusion.

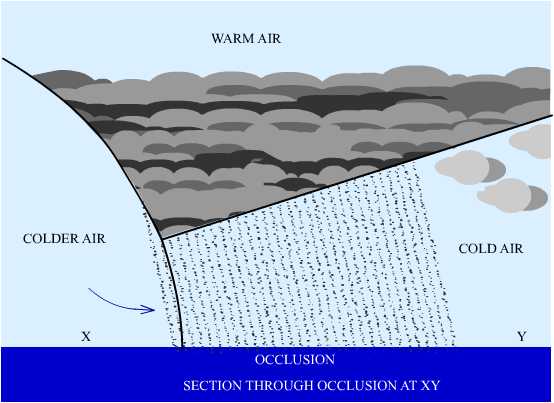

If the depression is occluded, the occlusion is

preceded by the cloud of the warm front; there may be a period of continuous

rain mainly in front of and at the line of the occlusion, or a shorter period

of heavy rain mainly behind the occlusion, according as the air in front of the

occlusion is colder or warmer than the air behind it. There may be a sudden veer (backing) of wind

at the occlusion.

Often another depression follows 12 to 24 hours later,

in which event the barometer begins to fall again and the wind backs towards SW

(NW), or even S (N).

If a depression travelling E or NE (SE) is passing S

(N) of the ship, the winds in front of it are E and they back (veer) though NE

(SE) to N (S) or NW (SW); changes of direction are not likely to be so sudden

as on the S (N) side of the depression.

In the rain area there is often a long period of

continuous rain and unpleasant weather with low cloud. In winter in the colder regions the weather

is cold and raw and precipitation is often in the form of snow.

Winds may be temporarily light and variable near the

centre of a depression but rapid changes to strong or gale force winds are

likely as pressure begins to rise and the low moves away.

Sometimes in the circulation of a large depression,

usually on the equatorial side and often on the cold front, a secondary

depression develops, traveling in the same direction as the primary but usually

more rapidly.

The secondary often deepens while the original

depression fills. Between the primary

and the secondary depressions, the winds are not as a rule strong but on the

further side of the secondary, usually the S (N) side, winds are likely to be

strong and they may reach gale force.

Thus the development of a secondary may cause gales farther from the

primary than was thought likely, while there may be only light winds where

gales were expected.

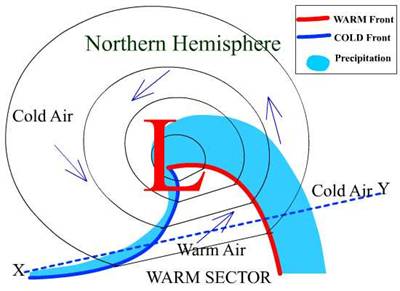

This is shown in the following diagram:

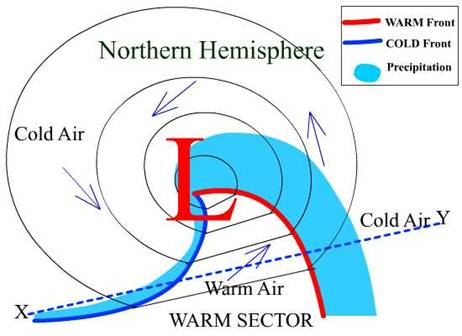

Depression Northern Hemisphere:

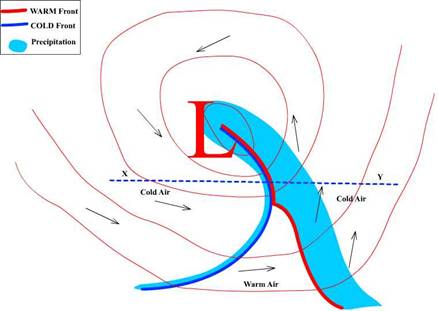

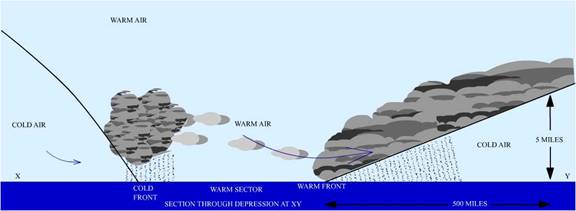

Warm air is lighter than cold air and rises over the

cold air ahead of the warm front as shown in the diagram:

This causes

condensation of the water vapour in the warm air, forming at first cloud and

later drizzle or continuous steady rain. The cloud spreads out ahead of the

warm front and the highest cloud, cirrus, is often about 500 miles ahead of it.

At the rear boundary of the warm sector, known as the cold front, the cold air

is pushing under the warm air forcing the latter to ascend rapidly.

This process is sometimes violent enough to produce

squalls. The rapid ascent of the warm air causes the moisture to condense in

the form of cumulonimbus clouds (shower clouds), from which heavy showers may

fall.

OCCLUSION

The cold front moves faster than the warm front and

gradually overtakes it, causing the warm air to be lifted up from the

surface. When this happens the

depression is said to be occluded and the fronts have merged into a single

front, known as an occlusion.

Occlusion Northern Hemisphere:

Occlusion Northern Hemisphere:

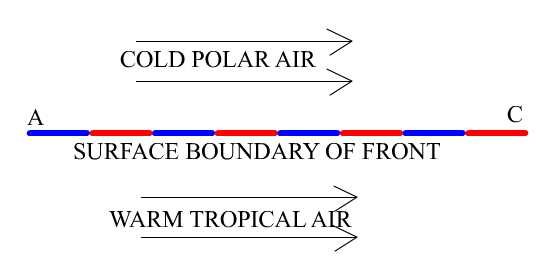

FRONT

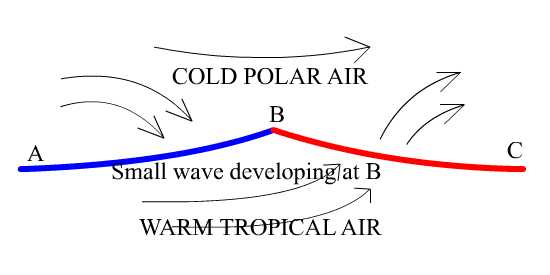

If two air masses from different regions, such as the

polar and tropical regions, are brought together, the surface boundary where

they meet is known as a front. Further there is a tendency for waves to form on

this front and some of these waves develop into depressions.

This is

shown in the diagram below:

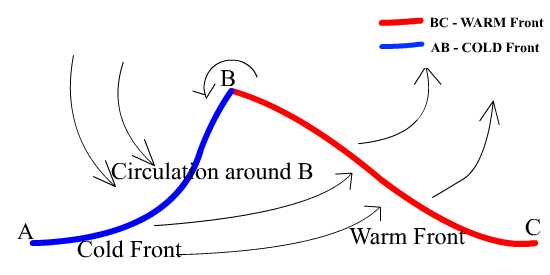

After sometime this surface boundary slowly takes the

form of a depression and has a circulation.

The part of the front marked AB is called a cold front

as along it cold air is replacing warm air. The part marked BC is the warm

front since along this front warm air is replacing cold air.

Oceanic

depressions usually have one or more fronts extending from their

centres, each front representing a belt of bad weather, ac companied by a veer

(backing) of wind, which marks the change from the weather characteristic of

one air mass to that of the other. During the first two or three days of its

existence a depression has a warm and a cold front, the area between the two

being known as the warm sector because the air has come from a warmer locality

than that which is outside the sector.

This is shown in the following diagram:

Depression Northern Hemisphere:

Warm air is lighter than cold air and rises over the

cold air ahead of the warm front as shown in the diagram:

These are intense depressions occurring in tropical

latitudes accompanied by high winds and heavy seas. Although the pressure at

the centre of a tropical storm is comparable to that of an intense mid-

latitude depression, the diameter of a tropical storm is much smaller (some 500

miles compared with 1,500 miles), and therefore the pressure gradients and the

wind speeds correspondingly greater.