| Sailings | Chart Work Exercises | Information from Charts | Tides | Sextant |

Terrestrial Navigation

Information from Charts

The

Chart Catalogue

Many countries publish Chart Catalogues.

Among the principal chart publishers is the Hydrographer

to the Navy (U.K.). However other countries that do publish charts also make

available data to the International Hydrographic Organisation, who allows

different countries to publish these charts. Thus the 2nd publishers just print from whatever data they get from the

IHO and the survey is conducted by the 1st country. These series are

termed International series and bear the stamp of the IHO.

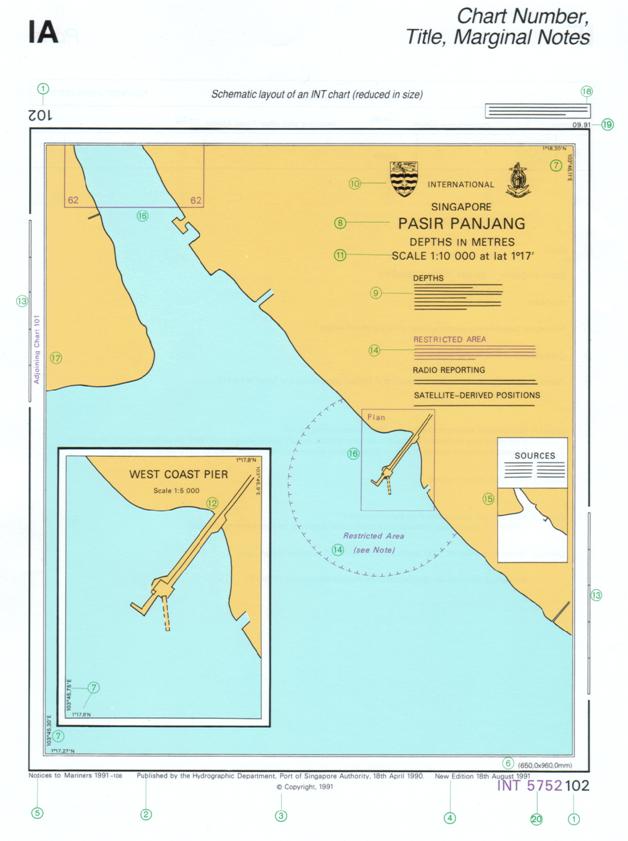

To give an example note

the label on the following:

Here you see the surveying country as

The charts that are published anywhere follow

the rules as laid down by the IHO, thus learning to use a chart of one country

makes one proficient in using other charts.

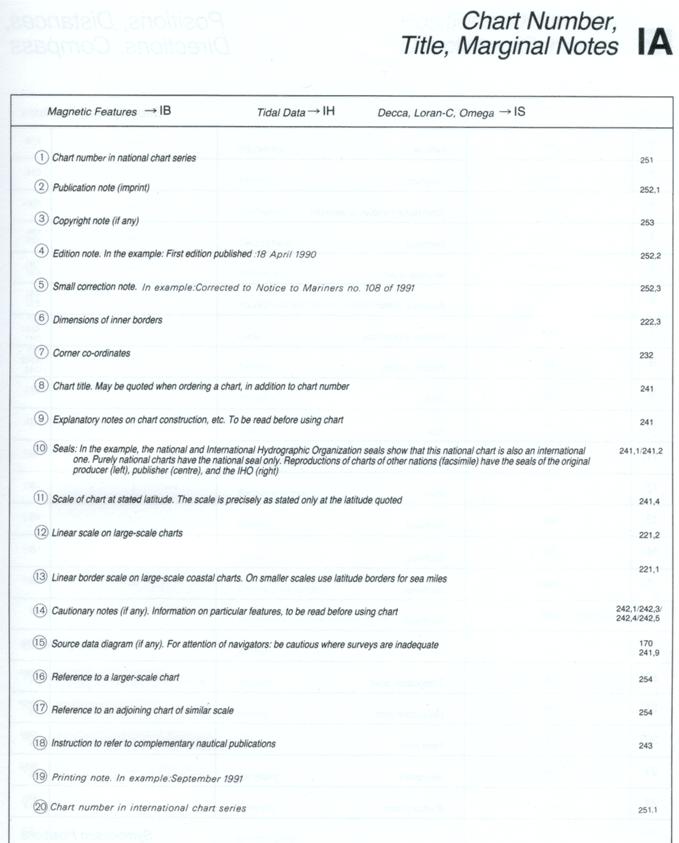

The above picture is self explanatory if

read in conjunction with the following picture:

Prior taking a new chart for use the

following must be checked:

- The

correction record at the bottom left hand corner

- The

year of publishing

- The

scale of the chart, and

- The

source table

The source table would give the type of

survey that was carried out and when. Many charts are published with some areas

being surveyed recently while in other areas the data is taken from previous

surveys (which may be quite old).

All International series charts have the

International number beside the national number of the chart.

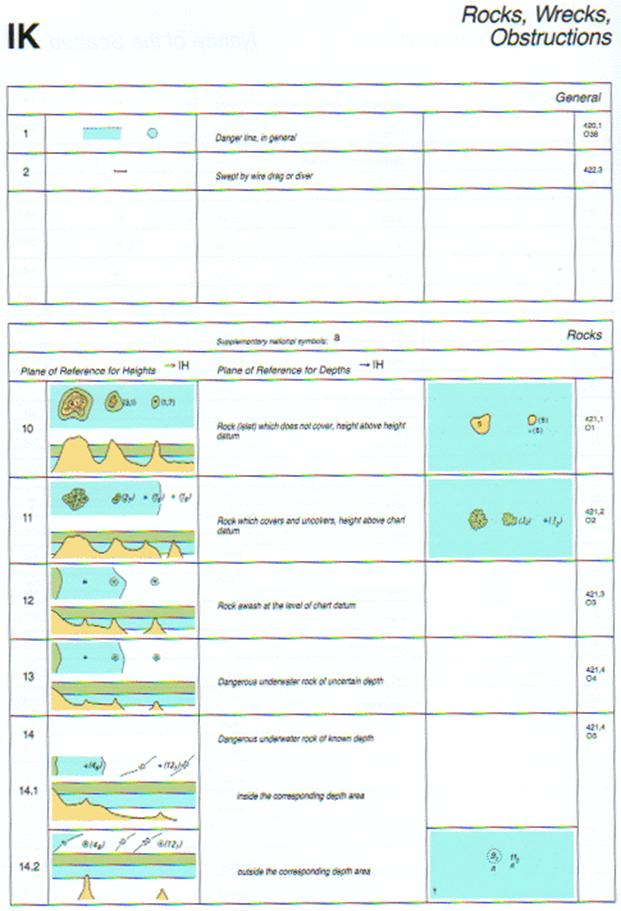

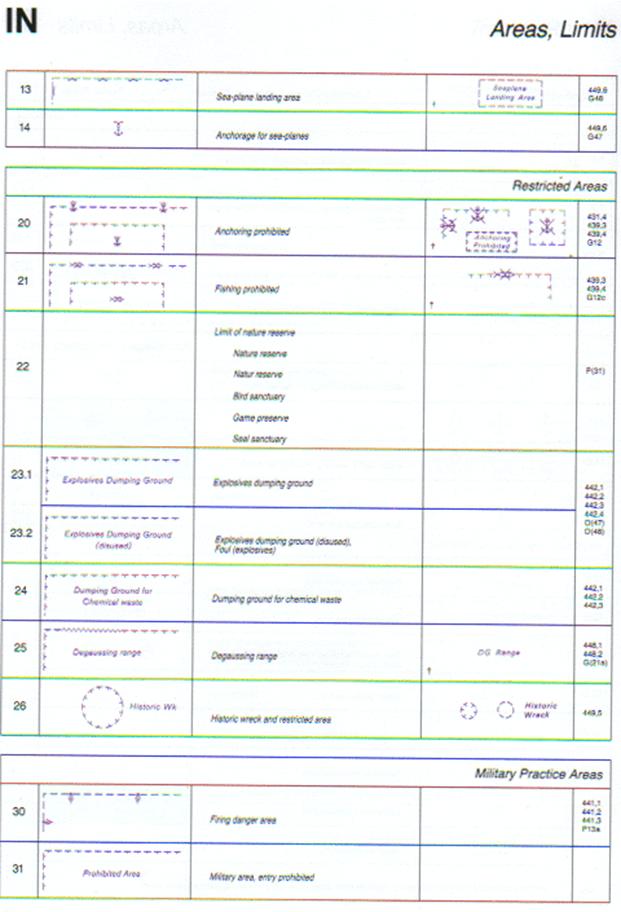

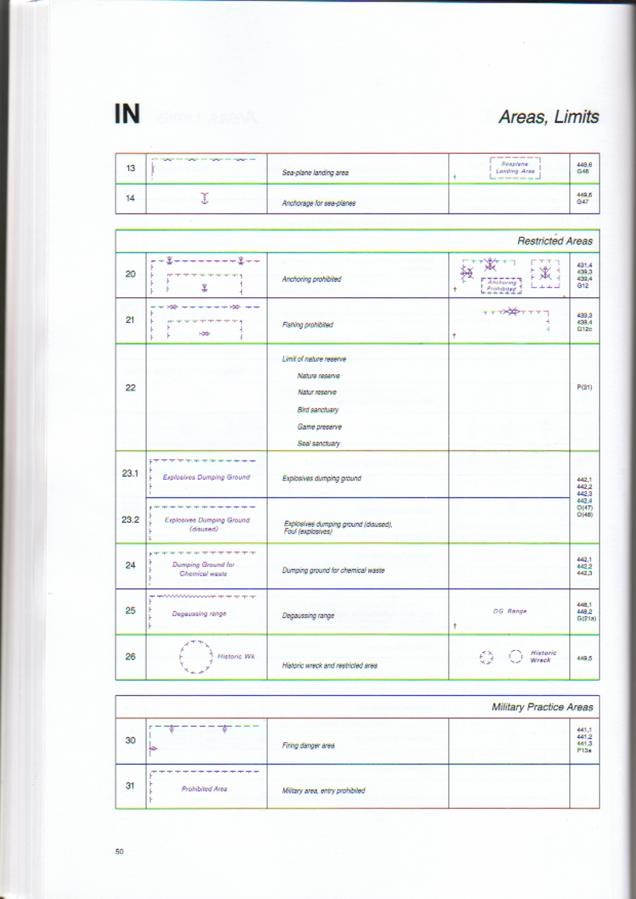

Learning

the symbols printed on the Charts:

While charts are published, the

abbreviations, the symbols and the colour code is not

mentioned on the charts and the mariner is expected to know of such things

prior to using the charts.

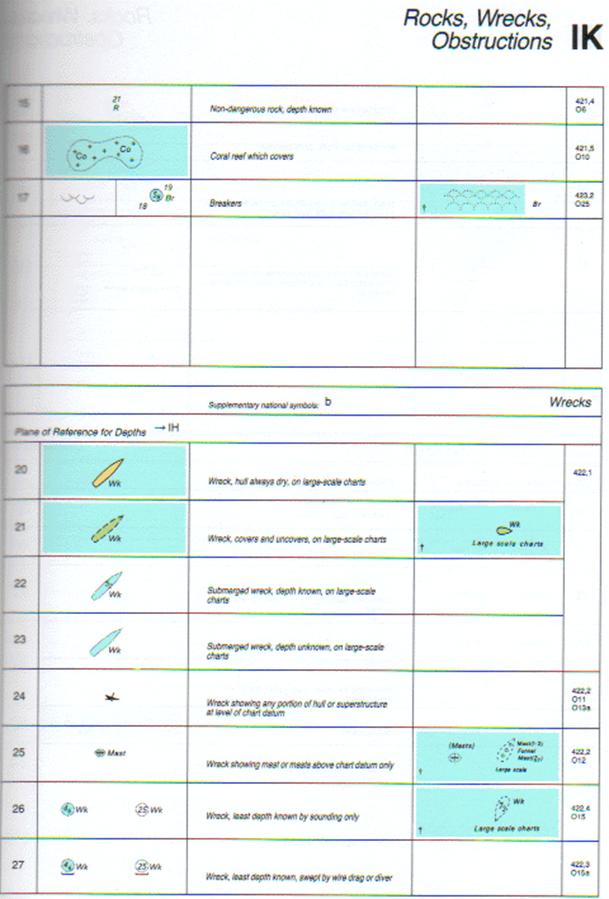

The above symbols and the abbreviations

are printed in another publication called Chart 5011 by the UK Hydrographic

office. Other countries do have such books.

To give an example of a few items:

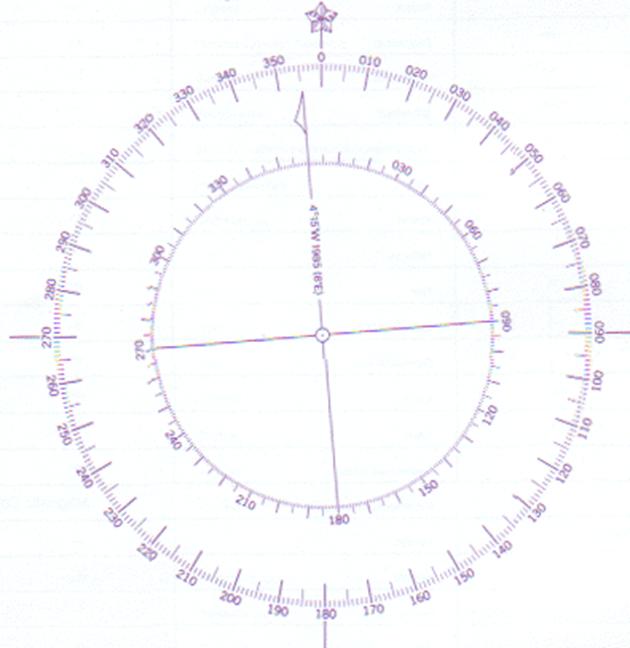

The above shows a compass rose. The circle

is always projected in the above manner, the top of the rose pointing to the

top of the chart.

The outer ring is the one from where the

true bearings are plotted.

Within the outer ring there is an inner

ring graduated in the same way but slightly off with reference with the outer

ring. This inner ring is the one that has not been compensated with the

variation.

Thus if the bearings that are plotted are

corrected only for deviation then these may be drawn using this ring

graduation.

The variation is again written on the

north marking line in this case is written as:

4°15 W 1985 (6°E)

Meaning that in 1985 the variation at that

place, where the rose is printed was 4°15West and that

the yearly change is 6°E. Now to get the variation for 2004, we have to

multiply the number of years since 1985 19 years with 6°

and get 114°. So 1°54 have to be

subtracted from 4°15W. Subtract since the change was E.

Passage Planning

Passage Planning is a way of minimising

the risk of navigational error. In areas

of high traffic density and restricted available water, the requirement for

pre-planning becomes even more necessary.

The aim of passage planning is to prepare for the

navigation of the ship so that the intended passage can be executed in a safe

manner in respect of both the vessels and the protection of the environment, by

ensuring the proper and positive control of the ship at all times. Without such planning, the time to process

essential information may not be available at critical times when the bridge

team is occupied in confirming a landmark, altering course, avoiding or

monitoring traffic and carrying out other bridge duties, such as external

communications and internal communications within the ship. Under these circumstances, unless there is an

effective plan in place, mistakes and errors may go undetected leading to

disastrous consequences.

The construction of an effective passage plan

encourages all those concerned to foresee potential problems and plan a

strategy to minimise the risk.

No specific courses are laid down as it is necessary

for all vessels to plan, and lay down on the chart, their own course.

Where alterations of course are required, the latitude

or longitude or approximate bearing to a navigational mark, which ever is more

appropriate, is used singly to indicate an obvious change of direction in the

traffic separation scheme. This to

ensure that navigators are not using a set of advised, fixed positions thus

avoiding vessels using exactly the same courses in their individually developed

plans.

Checklists

The Checklists are a basis for individual ships either

amending or drawing up their own checklists.

They should not be considered to be definitive but the basis for

individual ships to expand upon. The

checklists incorporate checks for readiness for transit and reporting.

Parallel

Indexing

This is the simplest and quickest pilotage

technique that gives continuous monitoring of the track that the ship is making

good. Parallel indexes should be used,

whenever practicable, while transiting through coastal areas. To this end, for every leg, suggested

reference points should be included into the Passage Notes. These points are known to be radar

conspicuous and likely to be available at all times. Buoys, especially buoys known to be prone to

damage or movement, should never be used.

Wheel Over Positions

Course alteration positions should be chosen to allow

for proper monitoring during ship turns.

Ships using a plan would have their maneuvering characteristics and the

ships data must thus be consulted when planning a wheel over position.

Where possible, techniques for monitoring the turn

should be used. This may be using a rate

of turn indicator, parallel indexing or other suitable techniques.

Emergency /

Contingency Plans

By preparing in advance for possible contingencies, a

quick and effective response can be made when the unexpected happens. Plans should be considered for coping with,

amongst others, steering failure, power loss, loss of propulsion or any other

type of accident or emergency that may occur on a ship that will affect the

navigational ability.

To this end, the Passage Notes, for each leg, should

indicate the available depth of water.

PASSAGE

PLANNING NOTES

The requirement for an effective plan is included in

the STCW Convention that states - "The

intended voyage shall be planned in

advance taking into consideration all pertinent information and any course laid down should be checked before

the voyage commences."

Purpose

The purpose of passage planning is to ensure control

over the safe navigation of the ship at all times. This is normally achieved by entering onto

the chart as much information as is available to enable immediate reference

should the unexpected occur. Also to monitor the progress of the vessel along the intended

tracks and within previously planned and agreed parameters.

Information

Required to Formulate a Passage Plan

Prior to compiling a passage plan as a minimum, the

following publications will be required in addition to this guide:

chart catalogue

corrected

navigational charts

routeing and pilot

charts

IMO Ship's Routeing

sailing directions

and pilot books

light lists

tide tables

tidal stream

information

Navtex local

warnings and Notices to Mariners (Navareas, Hydropacs) radio signal information (including VTS and

pilot service) owner's and other unpublished sources

manoeuvring data

Mariner's Handbook

climatic

information and weather forecasts electronic navigational systems information

(as applicable) personal experience of ships navigating officers.

Additionally, when compiling the passage plan the

availability and reliability of the following have to be considered at the

early part of the planning phase:

main propulsion

system

steering gear

navigational equipment

anchors

thrusters (if

equipped)

auxiliaries

trim and

draught of vessel

transverse stability

the availability

of manpower.

Preparing

the plan

When preparing the plan the

navigating officer will need to take account of the following:

a.

Adequate under keel clearance at all times, including

allowances for squat, pitch, roll, swell, predicted tidal height and possible

increase of draught due to heel and trim

b.

safe distances off dangers, allowing for weather,

tidal stream, anticipated traffic, availability of safe water and navigational

systems in use

c.

alter-course positions which can be monitored

conveniently either visually or by radar

d.

management of chart changes, which should not occur at

critical points of the passage

e.

The Traffic Separation Schemes, and the requirements

of Rule 10

f.

predicted tidal stream information, leading to the

pre-working of allowances for set

g.

visibility of lights (especially in the Malacca

Straits), rising/dipping distances, arcs and colours of light sectors

h.

envisaged safe speeds along the route, taking into

consideration recommended area of reduced speed, leading to a speed plan for the

transit, and an ETA plan at the pilot station or

i.

storing position,

making due allowance for possible reduced visibility. A plan for reducing speed

under control should be considered

j.

selection of depths for comparison with the echosounder, taking note of the predicted height of tide

may be desirable for certain routes

k.

reporting points,

VHF frequencies, VTS requirements, areas of special concern and pilot station

frequencies if either requiring a pilot or areas of increased traffic density.

l.

abort positions for specific sections and contingency

plans in case of accident or emergency or bad visibility

m.

the primary and secondary systems of navigation to be

used

n.

requirements of any electronic chart systems

o.

all charts and publications available are up to date

p.

equipment status

q.

margins of allowable error, safety clearing bearings

and ranges

r.

the making up

of a bridge, or conning, notebook.

The master must satisfy himself that the passage plan

meets all his requirements and he must then ensure that all watch-keeping officers

are properly briefed; and that the plan is kept amended and upto-date for the

intended passage.

Passage

planning therefore should be a preparation for effective piloting by selecting,

and marking in advance,

those relevant navigational techniques which will lead to safe control of the ship and adherence to the plan.

Parallel

Indexing

As mentioned previously this is the simplest and

quickest pilotage technique, and is highly

recommended as it gives continuous monitoring of the track that the ship is

making good As with all radar techniques, parallel indexing should be practised in clear weather during straightforward passages

so that personnel become thoroughly familiar with the technique before

attempting to use it in confined or difficult passages, at night or in

restricted visibility. Great care should

be taken in identifying and confirming reference points on the chart and on the

radar; and also in verifying the radar range when using the parallel index.

Preparing

the Chart

1 .The first

step when preparing a passage plan is to identify and mark the 'no-go' areas on

the chart.

The charts supplied to ships are the same for

everyone, whether for use on board a VLCC at 25 metres draught or on a coaster

sailing at 3 metres draught. It is

therefore imperative that the chart is made suitable for the specific condition

of your vessel. This should be done by

marking the 'limiting danger lines' - often referred to as marking out the

'no-go areas.'

These are valuable safety limits to any plan for a

coastal. Lines must be drawn on the

chart to highlight where the vessel cannot go.

Proper allowance must be made for maximum draft and predicted tidal

height and any other limiting condition.

The concept of marking no-go areas has the following benefits:

a.

it forces consideration of the factors affecting under

keel clearance, which is always the high risk element

b.

it forces a

concentrated study of the chart, rather than just a glance it immediately highlights to anyone who looks at the chart the,

often large, areas that must be avoided.

It is not enough to depend on, say, printed depth

contour lines. The lines have to be

prominent in order to highlight the immediate danger quickly and effectively at

any time under any light condition.

It is important to draw the no-go boundaries as

accurately as possible. They should

show, for example, that the vessel can pass the wrong side of a mark, in an

emergency, although this may not normally be desirable. It can be seen from the study of some recent

incidents that had this information been immediately available, then a grounding or collision would most probably not have

occurred. In this context passing the

wrong side of a buoy is nothing compared with the consequences of even a minor

incident.

Insert the 'limits of safety'. Normally this will be an area either side of

the vessels intended track that may be acceptable to deviate within, under

normal circumstances. In the approaches

to ports as well as in some areas, however, this may be the traffic lanes

already on the chart. However in certain

areas, additional lines should be marked on the chart to highlight where it has

been considered that it is only safe to navigate under normal circumstances.

After these considerations have been made the vessels

intended track should be inserted.

The wheel over positions should then be marked on the

chart. When marking the wheel over

positions consideration should be given to the amount of rudder that will be

applied, the expected speed of the ship at the alteration position and also the

depth of water due to the effect on the turning circle of shallow water,

It is often valuable to insert the speed that is to be

maintained along certain sections of a leg.

This is especially true if an accurate ETA is required at a certain

point, e.g. for picking up pilots or rendezvousing for stores.

The methods to be used for fixing the vessels position

on different parts of the intended track should be entered onto the chart. The prime method should be by visual fix,

whenever possible, backed by radar or electronic means. If, from experience, it is known that there

are conspicuous landmarks or points for position fixing it is often worthwhile

to identify these.

The timing of fixing the vessels position should be

considered when passing though the congested waters. The requirement for fixing the vessels

position will vary considerably, based on the nearness of the most imminent

danger and also while executing and completing a turn. As a back up to frequent fixing, the use of

parallel indexing techniques will assist in ensuring the vessel is maintaining

the intended track and should be considered, especially in the more constricted

parts.

From experience it will become evident what

identifiable marks are radar conspicuous. It is of value to mark these radar

conspicuous targets on the chart for future reference. Weaker targets that may be usefully used in

clear weather may disappear in heavy rain and thus may not be available.

Clearing bearings for hazards, and to assist in

maintaining the track should be inserted onto the chart. These give a very quick method of checking

that the vessel is, at least, missing dangerous or noteworthy points.

Clearing ranges are another technique used by some

vessels to ensure that a minimum and maximum distance is maintained from a identifiable mark.

These should be considered on all vessels where parallel indexing is not

being employed and may especially beneficial when completing a turn.

Prior to entering a restricted section abort points

should be entered on the chart. At this

point it must be agreed that to proceed any further all systems etc. have to be

fully operational and the vessel is in readiness to proceed. As well as entering the abort point on the

chart it is often recommended that the action to be taken to abort is also

entered onto the chart. E.g. When reaching the abort point the engine speed is reduced

and the direction of turn, with possibly the helm order, entered so that all

personnel involved in navigating the vessel are fully aware of the agreed

action to be taken.

In addition to the abort positions contingency

planning should also take place whilst compiling the passage plan. By marking the "no-go areas" on the

chart, as suggested above, it should be readily apparent if there is sufficient

water outside the traffic lanes in which to anchor. By preparing in advance for possible

contingencies, a quick and effective response can be made when the unexpected

happens. Plans should be considered for

coping with, amongst other things, main engine failure, steering loss, port or

channel closures, radar failure, reduction in visibility, heavy traffic at

crucial points, movement or closure of a pilot station, or any of the accidents

and emergencies that can occur to a ship on passage.

The tidal streams and heights at the time of expected

transit should be marked on the chart.

The depth of water, in general, at sea should not pose a problem for

vessels, but if the height of tide is marked on the chart, in coastal waters it

will assist in contingency planning. The

direction and strength of the tide and current in certain parts,

can be very strong and should be marked on the chart in prominent

positions. This will assist, not only,

in predicting and understanding the movement of your own ship but also the

movement of others, especially slow moving vessels and tugs with tows.

In addition to the above it is suggested that the

reporting points are clearly marked on the chart, in addition to the positions

where it is necessary to change VHF channels.

Also the position of expected high traffic density

should be marked on the chart along with any other relevant information.

Monitoring

the Passage Plan

It is common practice to fix the ship's position and

then make an allowance for set and drift depending upon offset from the

previous fix. This approach to

navigation is REACTIVE, being based upon past observations. If either of these is wrong, then any

predictions using them will be erroneous.

When using fixes in this way, it is usually better to make the fixes at

regular and appropriately frequent intervals.

This enables a simple check to be made with respect to speed. It also helps the quick and effective

calculation of short-term EPs (Estimated Positions), using the latest course

and speed made good, to warn of any immediate problems developing.

However, in narrow and restricted waters, techniques

need to be used which enable the navigator to maintain a forward outlook, that is to be PROACTIVE, whilst monitoring the

deviation from the intended track being made good. Frequent, hurried visits to the chart table

to fix the vessel's position may not be the most effective use of the time

available. Also, whilst doing this the

overall sense of awareness can be interrupted and it is easy, during critical

phases, to become disorientated.

It is worth remembering to monitor the

echo-sounder. This instrument can often

provide the first warning signs that the vessel is standing into danger, since

in almost all situations the nearest land is beneath the vessel.

PASSAGE PLANNING

CHECKLIST

Charts

Are the charts the largest scale available?

Are they corrected for the latest Notice to Mariners and local navigational warnings?

Do the charts completely cover the area?

Sailing

Directions

Is the planned track following recommended routes?

Is the plan

following local regulations?

Are all potential hazards known?

Port /

Storing Information

Are local conditions known?

Is berthing / storing information available?

Tidal

Atlas/Tables

Have the stream strength and directions been discussed?

Have the tidal heights been discussed?

List of

Radio Signals

Where is the pilot boarding area?

Are

Where are the required calling

in points?

Weather

Reports

Is the local forecast available?

Local Agent

Has the agent advised of berth and berthing/stores and

storing requirements?

Vessel

Condition Comments

What is the draft and air draft?

What is the minimum acceptable underkeel

clearance?

Manoeuvring

Data

Have considerations for squat been made and are tables

available?

Chart

Information

No-go areas

Margins of safety plotted

Plotted tracks

Have we calculated the wheel-over points and what are

they?

Parallel index references

Required speed at differing way points

Tidal stream anticipated

Crew call out position

Tug meeting area

Abort positions

Contingency plans available?

Briefing

Were all navigators present?

Have the fixing intervals been determined?

Have fixing points been determined?

Have the primary navigation aids been determined?

Have the secondary means been discussed?

Have the areas of high risk been determined and

discussed?

Has the bridge team discussed the information flow and

has it been agreed?

Has the charted plan been discussed?

Has the watch condition been determined?

Have duties been assigned and understood?

Have the conditions for increasing the watch been

determined?

Have team members been made aware of any defective

equipment?

Buoyage

International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation

and Lighthouse Authorities (IALA)

The IALA buoyage system is

split into 2 regions A and B. Region B is mostly areas of the world with

American influence, Region A is mostly countries with

IALA Buoyage System A and B

Visibility

of Lights:

Lights are placed on Light Houses at a

height of the light houses, depending on the intensity of the lights

themselves, the lights are marked as visible up to a distance of a certain

limit, the height of the observer when declaring the above is taken to be 15

feet (4.5 metres).

However the visibility of the lights at

the marked limit may be exceeded due to the height of the ship also.

The expression for obtaining the raising

of the light limit is given by:

Heights in feet:

Distance = (√Height of observer x

1.15) + (√Height

of Object x 1.15)

Heights in metres:

Distance = (√Height of observer x

2.083) + (√Height

of Object x 2.083)

Or

Distance = (√Height of observer x 2.1) + (√Height of Object x 2.1)

Example:

Assume the following:

Height of eye (Bridge): 21 m

Height of Light House (from List of

Lights): 60 m Range: 20 NM

Then the above equation would be as

follows:

Distance = (√Height of observer x

2.1) + (√Height

of Object x 2.1)

Distance = (√21 x 2.1) + (√60 x 2.1)

Distance = (4.58 x 2.1) + (7.75 x 2.1)

Distance = 25.9 NM

That is the light would be seen from a

distance of 26 NM.